Human Computer Interaction

4.5. Usability principles relating to mātāpono Māori

This field guide is written to support students in Aotearoa | New Zealand to prepare for NCEA assessments, and one aspect of that is to be able to apply usability principles relating to mātāpono Māori - considerations that embed Māori culture. While this may seem to apply primarily within Aotearoa, there are a number of principles that come up that apply across cultures, and are widely relevant, particularly considering that interfaces (whether websites, apps or other types of software) are often developed in one culture, but used by people from many cultures. The ideal is that digital products and services should be usable for everyone, which is sometimes called “universal usability”.

To make sure an interface works for people from a particular culture, you need to understand the values of the culture. A Māori world view would generally include the following:

- manaakitanga, which is based on the word “mana” - upholding a person’s mana, or showing respect for them;

- rangatiratanga, the right to exercise authority and self determination,

- whanaungatanga, building relationships with people, which usually starts with finding common connections through places and people,

- aroha, which is about empathy, and compassion for others, and

- kaitiakitanga, which is guardianship and protection of the resources entrusted to you.

These descriptions give you a broad idea of their meaning, although living and enacting these is much deeper than can be written here.

These are valuable human traits in general, but if we look at them through the lens of HCI, they are a remarkable summary of what makes a good interface! Manaakitanga is key; an interface should raise a person’s mana by helping them to achieve their goals. Conversely, if an interface constantly gets in the way of what someone is trying to do, making it hard for them to see where to click next, or making it easy for them to have slips or make mistakes, it is pulling down their mana, and is certainly not exercising manaakitanga.

Similarly, an important usability principle is “user control and freedom” - that users should be able to get out of unwanted states and not be boxed into a corner, or even better, undo the result of an incorrect choice. This relates directly to rangatiratanga - the user should be able to determine what they want to achieve, and not be constantly thwarted by the system.

When designing interfaces, it is key to understand your users; this is whanaungatanga and aroha in action. What are their goals for using your software? What do they do on a typical day? What environment are they working in, and what time constraints might they have? Great interfaces come from understanding your user and having empathy for them, rather than blaming them for errors they make using your interface.

Being a software developer is a privileged position; it is rare that a user has much control over the design of the software and apps that they use. The developer needs to appreciate their role as kaitiaki (guardian) of the product that is being used by thousands or even millions of users. While they can’t fully understand every user, they need to be diligent about valuing those people, and make sure that any updates are done bearing in mind the best interests of their community of users.

An immediate consideration for usability of interfaces is the use of language. If users have te reo Māori (the Māori language) as their first language, then information presented in English may be confusing. An important usability principle is that a “system should speak the users' language, with words, phrases and concepts familiar to the user”; normally this is in the context of avoiding jargon and obscure phrases, but of course it also means that it should use the written language that the user is comfortable with.

One study of an interface for online access to Māori niupepe (newspapers) found that when users were able to interact with the system in te reo Māori they made 21% more usage requests, and made better use of the system. For some people, the interface was harder to use for them than in English, but they were proud to be using their language, and some still chose to use it even if it was slower.

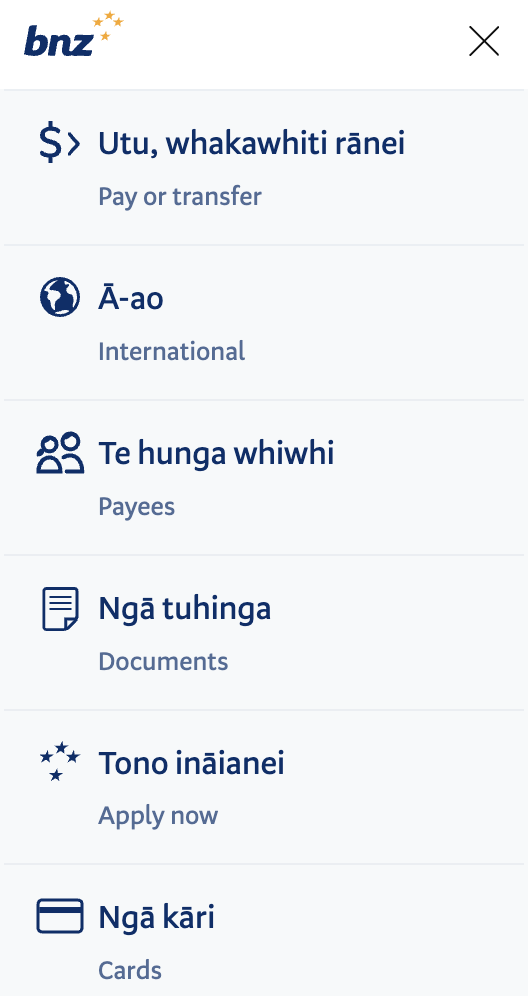

One way to empower users is to have a version of the interface available for learners of the new language. It might show most terms in both languages, allowing users to learn the corresponding terms, and then allow them to switch to a full immersion version once they are familiar with the terms. For example, BNZ offer this feature in their online banking, which both gives mana to the language, but also supports those who aren’t confident using the language (particularly since a small misunderstanding could lead to a significant financial consequence!)

The importance of supporting a user's own language implies having the interface translated, but translations need to be done with care; you can’t just look a word up in a dictionary and substitute it, since translations rarely have exactly the same meaning, the choice may depend on the context, or the correct word might be ambiguous and therefore confusing. For example, a button labeled “Play” would have a different meaning for a game (“hākinakina”) or for playing music (“whakatangi”). Also, the technical terms being used in an interface (such as “File”, “Open” and “Delete”) may use terms that everyday speakers of te reo aren’t familiar with, and this is another important consideration in how to present the interface. Note that it isn’t just the menus and buttons that need translating; installation instructions, error messages and help information are important, and may be considerably more work than just changing the surface elements of the interface.

It also means that the interface needs to be able to use the character set of the user’s language. If the user is entering text as input, it needs to be possible to easily see how to enter all characters in the language. In te reo Māori, tohutō (macrons over a vowel, ā, ē, ī, ō and ū) are particularly important because they give guidance on how words should be correctly pronounced, and they indicate which particular Māori word is being used. Some factions in certain dialects have alternative orthographies for the lengthened vowel, but the tohutō is the universally accepted method.

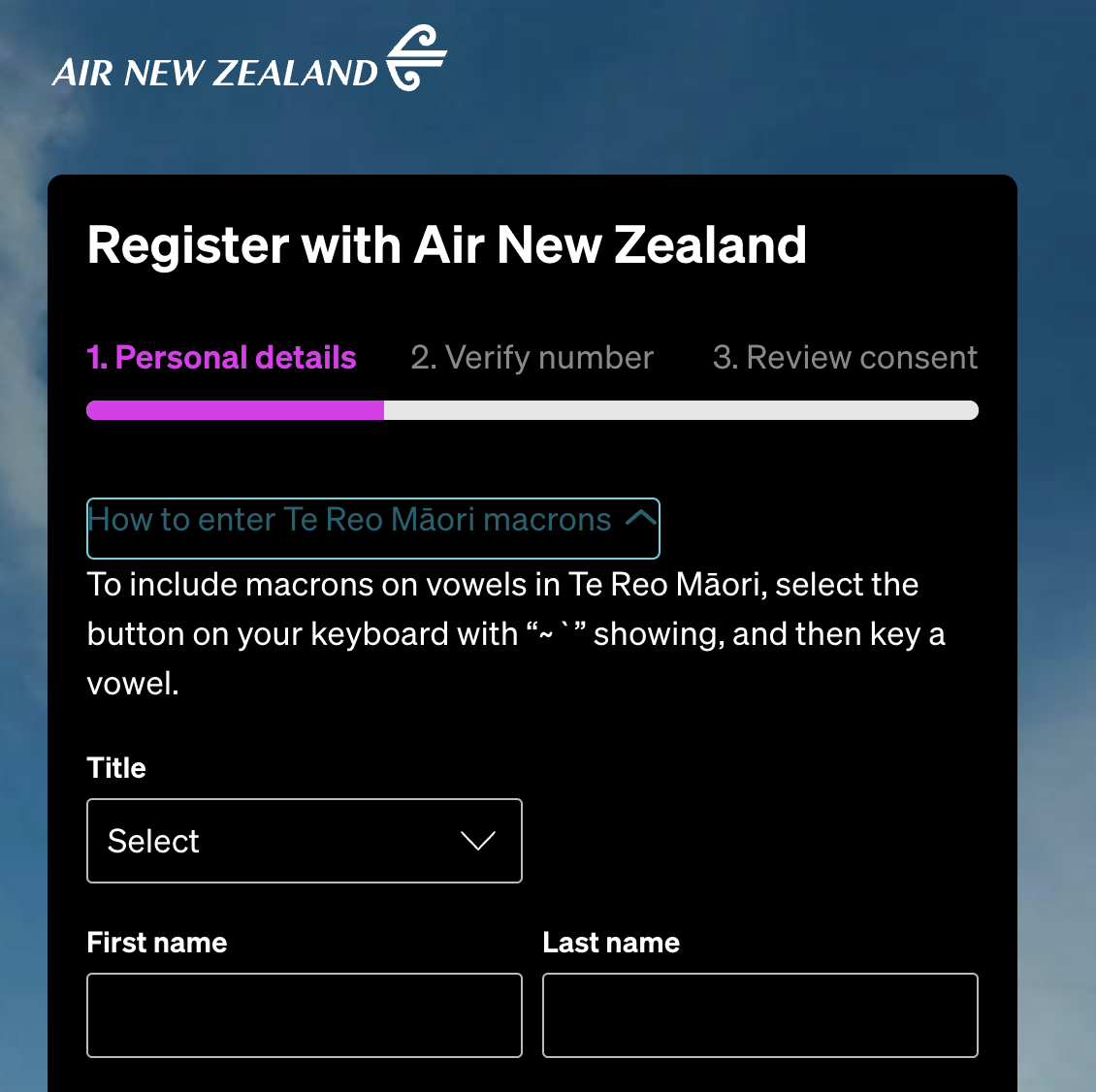

Have a look online at systems that ask for your name (particularly if you are registering an account). Is it obvious how to type a name with a tohutō | macron in it? For example, Air New Zealand has instructions up front on how to do this, and it works without having to change device settings.

You may have come across the idea of using double vowels instead of macrons, such as Maaori instead of Māori. This was an early accommodation, largely due to technical limitations of early computers that used only 7-bit ASCII, and a particular academic, Bruce Biggs, who advocated the use of the double vowel to get around the limitation. ASCII stands for “American Standard Code for Information Interchange”, and only allows for the common characters used in America! The double vowel is still used by certain entities in Waikato, but there is a national standard for the use of tohutō (macrons), and since the turn of the century most computers have been able to produce the characters properly, so it’s no longer necessary to adopt the use of the double vowel writing system. Even if tohutō are possible in a system, some fonts may not have it available, and the substitute another font, which can reduce the mana of how the word is presented. For example the spelling in the word “whānau” below is correct, but the forced font substitution makes it look amateur.

One widely used system that hasn’t allowed the use of macrons is airline ticketing. This can be traced back to legacy systems to that were based on the ASCII character code; the “A” in ASCII stands for “American”, and inevitably focussed on characters and symbols used in just one region of the world. The limited character set in airline ticketing systems means that if your correct name was “Te Pō”, you would have to book it as “Te Po” (which is a different name), or use letter doubling to show this, and so write “Te Poo”. Having your name shown differently because of a bad interface is insulting (even if it doesn’t spell an insulting word!); even away from computers it’s important to get someone’s name right, and changing someone’s name deliberately is often intended as an insult. One case where an organisation made this mistake with their own name was Wētā digital; the company name used to be written as “Weta” instead of “Wētā”. You can look up the meaning of the two words to find out how embarrassing the mistake was.

A related issue is that the URL for a web page might not use tohutō; for example, the wētāFX company uses the URL wetafx.co.nz, without the tohutō. It is possible to support the use of tohutō in a domain name, but it requires extra effort, and does bring additional security risks if a user ignores the macron when typing the name (they may end up on a site that is cybersquatting). Doing things correctly involves many considerations, and it is typical in interface design that fixing one problem creates another!

Another consideration with text is that when users are entering text into an interface, often it will have spelling checking or correction available, and this needs to work properly for the user’s language. It is frustrating if the user has gone to the trouble of typing a word correctly with macrons only to have it automatically “corrected” by a predictive text system to the nearest similar English word; and it is confusing if correctly spelled words are marked as errors, since this makes it harder to notice actual errors.

Designing an interface that is culturally appropriate is very challenging. Unless you are immersed in the culture, it isn’t appropriate to take imagery or language just because it seems to add a nice touch to the site. For example, with images, the whakapapa (history and source) is very important, and will often be connected to a particular iwi or person. Any work using imagery and text needs to follow appropriate tikanga (rules and processes), and should involve people who are genuinely in a position to speak for the group from whom the material is sourced. This issue goes beyond copyright, and involves showing respect (manaaki) for those to whom the material has deep meaning.

If you are evaluating an interface that uses cultural symbolism or language, see if the organisation explains how they came to use it. The explanation should reflect consultation with those from whom the imagery originates, and the meaning of the imagery should be reflected in the culture of the organisation. For example, in the Air New Zealand recruitment material, they explain that “...our koru encourages us to take pride in our heritage; to face each challenge with confidence and determination. It reminds us too of the people and land that make our home special and our responsibility to nurture and maintain these precious resources for our future generations.” An example of missing the mark with this was a campaign by a soft drink company that used the phrase “Kia ora mate”, which to English speakers looks like a friendly greeting. However, to a te reo speaker, the word “mate” relates to death, and the first impression from the phrase is a lot less friendly!