It is recommended that you work through the chapter on algorithms first if you aren’t familiar with the idea of the complexity of an algorithm, or sorting algorithms. The ideas in this chapter build on the chapter on algorithms.

Complexity and Tractability

12.2. Algorithms, problems, and speed limits

Algorithms Curiosity

Complexity is an important concept with problems and algorithms that solve them. Usually complexity is just the amount of time it takes to solve a problem, but there are several ways that we can measure the "time". Using the actual time on a particular computer can be useful, but to get a rough idea of the inherent behaviour of an algorithm, computer scientists often start by estimating the number of steps the algorithm will take for n items. For example, a linear search can end up checking each of n items being searched, so the algorithm will take n steps. An algorithm that compares every pair of values in a list of n items will have to make comparisons, so we can characterise it as taking about steps. This gives us a lot of information about how good an algorithm is without going into details of which computer it was running on, which language, and how well written the program was. The term complexity is generally used to refer to these rough measures.

Having a rough idea of the complexity of a problem helps you to estimate how long it's likely to take. For example, if you write a program and run it with a simple input, but it doesn't finish after 10 minutes, should you quit, or is it about to finish? It's better if you can estimate the number of steps it needs to make, and then extrapolate from the time it takes other programs to find related solutions.

Asymptotic complexity Jargon Buster

If you're reading about complexity, you may come across some terminology like Big O notation and asymptotic complexity, where an algorithm that takes about steps is referred to as . We won't get into these in this chapter, but here's a little information in case you come across the terms in other reading.

Big O notation is a precise way to talk about complexity, and is used with "asymptotic complexity", which simply means how an algorithm performs for large values of n. The "asymptotic" part means "as n gets really large" – when this happens, you are less worried about small details of the running time. If an algorithm is going to take seven days to complete, it's not that interesting to find out that it's actually 7 days, 1 hour, 3 minutes and 4.33 seconds, and it's not worth wasting time to work it out precisely.

We won't use precise notation for asymptotic complexity (which says which parts of speed calculations you can safely ignore), but we will make rough estimates of the number of operations that an algorithm will go through. There's no need to get too hung up on precision since computer scientists are comfortable with a simple characterisation that gives a ballpark indication of speed.

For example, consider using selection sort to put a list of n values into increasing order (this is explained in the chapter on algorithms). Suppose someone tells you that it takes 30 seconds to sort a thousand items. Does that sound like a good algorithm? For a start, you'd probably want to know what sort of computer it was running on – if it's a supercomputer then that's not so good; but if it's a tiny low-power device like a smartphone then maybe it's ok.

Also, a single data point doesn't tell you how well the system will work with larger problems. If the selection sort algorithm above was given 10 thousand items to sort, it would probably take about 50 minutes (3000 seconds) – that's 100 times as long to process 10 times as much input.

These data points for a particular computer are useful for getting an idea of the performance (that is, complexity) of the algorithm, but they don't give a clear picture. It turns out that we can work out how many steps the selection sort algorithm will take for n items: it will require about operations, or in expanded form, operations. This formula applies regardless of the kind of computer it's running on, and while it doesn't tell us the time that will be taken, it can help us to work out if it's going to be reasonable.

From the above formula we can see why it gets bad for large values of n : the number of steps taken increases with the square of the size of the input. Putting in a value of 1 thousand for n tells us that it will use 1,000,000/2 - 1,000/2 steps, which is 499,500 steps.

Notice that the second part (1000/2) makes little difference to the calculation. If we just use the part of the formula, the estimate will be out by 0.1%, and quite frankly, the user won't notice if it takes 20 seconds or 19.98 seconds. That's the point of asymptotic complexity – we only need to focus on the most significant part of the formula, which contains .

Also, since measuring the number of steps is independent of the computer it will run on, it doesn't really matter if it's described as or . The amount of time it takes will be proportional to both of these formulas, so we might as well simplify it to . This is only a rough characterisation of the selection sort algorithm, but it tells us a lot about it, and this level of accuracy is widely used to quickly but fairly accurately characterise the complexity of an algorithm. In this chapter we'll be using similar crude characterisations because they are usually enough to know if an algorithm is likely to finish in a reasonable time or not.

If you've studied algorithms, you will have learnt that some sorting algorithms, such as mergesort and quicksort, are inherently faster than other algorithms, such as insertion sort, selection sort, or bubble sort. It’s obviously better to use the faster ones. The first two have a complexity of time (that is, the number of steps they take is roughly proportional to ), whereas the last three have complexity of . Generally the consequence of using the wrong sorting algorithm will be that a user has to wait many minutes (or perhaps hours) rather than a few seconds or minutes.

Here we're going to consider another possible sorting algorithm, called permutation sort. Permutation sort says "Let’s list all the possible orderings (permutations) of the values to be sorted, and check each one to see if it is sorted, until the sorted order is found". This algorithm is straightforward to describe, but is it any good?

Permutation sort is no good in practice! Teacher Note

Note that permutation sort is not a reasonable way to sort at all; it's just an idea to help us think about tractability. It should be obvious to students fairly quickly that it's grossly inefficient. The main thing is that is does produce the correct result, so it's an extreme example of an algorithm that works correctly, yet is way too inefficient (intractable) to be useful.

For example, if you are sorting the numbers 45, 21 and 84, then every possible order they can be put in (that is, all permutations) would be listed as:

45, 21, 84

45, 84, 21

21, 45, 84

21, 84, 45

84, 21, 45

84, 45, 21

Going through the above list, the only line that is in order is 21, 45, 84, so that's the solution. It's a very inefficient approach, but it will help to illustrate what we mean by tractability.

In order to understand how this works, and the implications, choose four different words (in the example below we have used colours) and list all the possible orderings of the four words. Each word should appear exactly once in each ordering. You can either do this yourself, or use an online permutation generator such as JavaScriptPermutations or Text Mechanic.

For example if you had picked red, blue, green, and yellow, the first few orderings could be:

red, blue, green, yellow

red, blue, yellow, green

red, yellow, blue, green

red, yellow, green, blue

They do not need to be in any particular order, although a systematic approach is recommended to ensure you don’t forget any!

Solution Teacher Note

For four different words, there will be 4x3x2x1 = 24 different orders for them. For example, there are 6 starting with "red", 6 starting with "blue", and so on.

Once your list of permutations is complete, search down the list for the one that has the words sorted in alphabetical order. The process you have just completed is using permutation sort to sort the words.

Now add another word. How many possible orderings will there be with 5 words? What about with only 2 or 3 words – how many orderings are there for those? If you gave up on writing out all the orderings with 5 words, can you now figure out how many there might be? Can you find a pattern? How many do you think there might be for 10 words? (You don’t have to write them all out!)

Solution Teacher Note

The number of orderings (permutations) for n words is the factorial of n; this is explained below, but basically there are n choices for the first word, n-1 for the next, and so on. For example, for 15 words, there are 15 x 14 x 13 x 12 x ... x 1 permutations, which is 1,307,674,368,000. It's a big number!

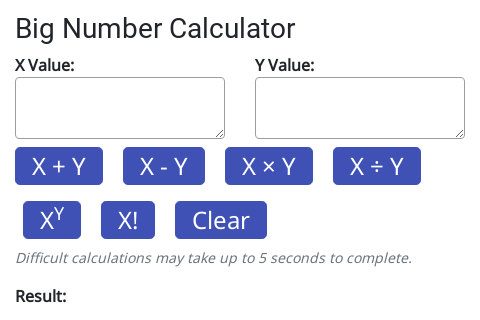

The factorial of a number can be calculated using a spreadsheet (in Excel the formula for is =FACT(15). A lot of calculators have a factorial button ("!"). You can even type into a Google search and get the answer. However, for dealing with very large numbers, the field guide has a simple calculator that can work with huge numbers; it is in the text below, or you can open it here:

For the above questions, the number of permutations are:

- 5 words: 120 permutations

- 2 words: 2 permutations (just the original two values and the reverse)

- 3 words: 6 permutations

- 10 words: 3,628,800 permutations

If you didn’t find the pattern for the number of orderings, think about using factorials. For 3 words, there are ("3 factorial") orderings. For 5 words, there are orderings. Check the jargon buster below if you don’t know what a "factorial" is, or if you have forgotten!

Factorials Jargon Buster

Factorials are very easy to calculate; just multiply together all the integers from the number down to 1. For example, to calculate you would simply multiply: 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 120. For you would simply multiply 8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 40,320.

As stated above, the factorial of a number tells you how many permutations (orderings) there would be for that number of words (assuming they are all different). This means that if you are arranging 8 words, there will be 40,320 ways of arranging them (which is why you weren’t asked to try this in the first exercise!!)

Your calculator may have a "!" button for calculating factorials and spreadsheets usually have a "FACT" function, although for the factorials under 10 in this section, we recommend that you calculate them the long way, and then use the calculator as a double check. Ensuring you understand how a factorial is calculated is essential for understanding the rest of this section!

For factorials of larger numbers, most desktop calculators won't work so well; for example, has 158 digits. You can use the calculator below to work with huge numbers (especially when using factorials and exponents).

Try calculating using this calculator – that's the number of different routes that a travelling salesman might take to visit 100 places (not counting the starting place). With this calculator you can copy and paste the result back into the input if you want to do further calculations on the number. If you are doing these calculations for a report, you should also copy each step of the calculation into your report to show how you got the result.

There are other big number calculators available online; for example, the Big Integer Calculator. Or you could look for one to download for a desktop machine or smartphone.

As a final exercise on permutation sort, calculate how long a computer would take to use permutation sort to sort 100 numbers. Remember that you can use the calculator that was linked to above. Assume that you don’t have to worry about how long it will take to generate the permutations, only how long it will take to check them. Assume that you have a computer that creates and checks an ordering every nanosecond.

- How many orderings need to be checked for sorting 100 numbers?

- How many orderings can be checked in a second?

- How many orderings can be checked in a year?

- How many years will checking all the orderings take?

Solution Teacher Note

The number of orderings for 100 numbers is , which is 93,326,215,443,944,152,681,699,238,856,266,700,490,715,968,264,381,621,468,592,963,895,217,599,993,229,915,608,941,463,976,156,518,286,253,697,920,827,223,758,251,185,210,916,864,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 permutations.

A nanosecond is 1/1,000,000,000 of a second, so the suggested system can check a billion orderings per second.

There are 60x60x24x365 seconds in a non-leap year, which is 31,536,000, so the proposed system could check 31,536,000 billion orderings in a year, so dividing 100! by this number, we get 2,959,354,878,359,467,043,432,877,944,452,901,461,527,015,736,440,310,168,334,378,611,593,658,041,388,569,114,946,139,776,006,992,588,985,721,014,739,574,573,764,941,185,024,000,000,000,000 years. That's an inconceivable amount of time, just to sort 100 values. This algorithm really is intractable!

And as an interesting thing to think about, do some calculations based on the assumptions listed below. How long would it take to use permutation sort on 100 numbers? What would happen first: the algorithm would finish, or the universe would end?

- There are atoms in the universe

- The universe has another 14 billion years before it ends

- Suppose every atom in the universe is a computer that can check an ordering every nanosecond

Solution Teacher Note

In the above example, the universe would end before the 100 numbers have been sorted!

By now, you should be very aware of the point that is being made. Permutation sort is so inefficient that sorting 100 numbers with it takes so long that it is essentially impossible. Trying to use permutation sort with a non trivial number of values simply won’t work. While selection sort is a lot slower than quicksort or mergesort, it wouldn’t be impossible for Facebook to use selection sort to sort their list of 1 billion users. It would take a lot longer than quicksort would, but it would be doable. Permutation sort on the other hand would be impossible to use!

At this point, we need to now distinguish between algorithms that are essentially usable, and algorithms that will take billions of year to finish running, even with a small input such as 100 values.

Computer scientists call an algorithm "intractable" if it would take a completely unreasonable amount of time to run on reasonably sized inputs. Permutation sort is a good example of an intractable algorithm. The term "intractable" is used a bit more formally in computer science; it's explained in the next section.

But the problem of sorting items into order is not intractable – even though the permutation sort algorithm is intractable, there are lots of other efficient and not-so-efficient algorithms that you could use to solve a sorting problem in a reasonable amount of time: quicksort, mergesort, selection sort, even bubble sort! However, there are some problems in which the ONLY known algorithm is one of these intractable ones. Problems in this category are known as intractable problems.

Towers of Hanoi Curiosity

The Towers of Hanoi problem is a challenge where you have a stack of disks of increasing size on one peg, and two empty pegs. The challenge is to move all the disks from one peg to another, but you may not put a larger disk on top of a smaller one. There's a description of it at Wikipedia.

This problem cannot be solved in fewer than moves, so it's an intractable problem (a computer program that lists all the moves to make would use at least steps). For 6 disks it only needs 63 moves, but for 50 disks this would be 1,125,899,906,842,623 moves.

We usually characterise a problem like this as having a complexity of , as subtracting one to get a precise value makes almost no difference, and the shorter expression is simpler to communicate to others.

The Towers of Hanoi is one problem where we know for sure that it will take exponential time. There are many intractable problems where this isn't the case – we don't have tractable solutions for them, but we don't know for sure if they don't exist. Plus this isn't a real problem – it's just a game (although there is a backup system based on it). But it is a nice example of an exponential time algorithm, where adding one disk will double the number of steps required to produce a solution.