This project is based around a scenario where there is a crayfisher who has around 18 craypots that have been laid out in open water. Each day the fisher uses a boat to go between the craypots and check each one for crayfish.

The crayfisher has started wondering what the shortest route to take to check all the craypots would be, and has asked you for your help. Because every few weeks the craypots need to be moved around, the fisher would prefer a general way of solving the problem, rather than a solution to a single layout of craypots. Therefore, your investigations must consider more than one possible layout of craypots, and the layouts investigated should have the craypots placed randomly i.e. not in lines, patterns, or geometric shapes.

When asked to generate a random map of craypots, get a pile of coins (or counters) with however many craypots you need, and scatter them onto an A4 piece of paper. If any land on top of each other, place them beside one another so that they are touching but not overlapping. One by one, remove the coins, making a dot on the paper in the centre of where each coin was. Number each of the dots. Each dot represents one craypot that the crayfisher has to check. You should label the top left corner or the paper as being the boat dock, where the crayfisher stores the boat.

Generate a map with 7 or 8 craypots using the random map generation method described above. Make an extra copy of this map, as you will need it again later.

Using your intuition, find the shortest path between the craypots.

Now generate a map (same method as above) with somewhere between 15 and 25 craypots. Make more than one copy of this map, as you will need it again later

Now on this new map, try to use your intuition to find the shortest path between the craypots. Don’t spend more than 5 minutes on this task; you don’t need to include the solution in your report. Why was this task very challenging? Can you be sure you have an optimal solution?

Unless your locations were laid out in a circle or oval, you probably found it very challenging to find the shortest route. A computer would find it even harder, as you could at least take advantage of your visual search and intuition to make the task easier. A computer could only consider two locations at a time, whereas you can look at more than two. But even for you, the problem would have been challenging! Even if you measured the distance between each location and put lines between them and drew it on the map so that you didn’t have to judge distances between locations in your head, it’d still be very challenging for you to figure out!

A straightforward algorithm to guarantee that you find the shortest route is to check all possible routes. This involves working out what all the possible routes are, and then checking each one. A possible route can be written as a list of the locations (i.e. the numbers on the craypots), in the order to go between them. This should be starting to sound familiar to you assuming you did the permutation sort discussed before. Just like in that activity you listed all the possible orderings for the values in the list to be sorted, this algorithm would require listing all the possible orderings of the craypots, which is equivalent (although you don’t need to list all the orderings for this project!).

How many possible routes are there for the larger example you have generated? How is this related to permutation sort, and factorials? How long would it take to calculate the shortest route in your map, assuming the computer can check 1 billion (1,000,000,000) possible routes per second? What can you conclude about the cost of this algorithm? Would this be a good way for the crayfisher to decide which path to take?

Make sure you show all your mathematical working in your answers to the above questions!

So this algorithm is intractable, but maybe there is a more clever algorithm that is tractable? The answer is no.

You should be able to tell that this problem is equivalent to the TSP, and therefore it is intractable. How can you tell? What is the equivalent to a town in this scenario? What is the equivalent to a road?

Since we know that this craypot problem is an example of the TSP, and that there is no known tractable algorithm for the TSP, we know there is no tractable algorithm for the craypot problem either. Although there are slightly better algorithms than the one we used above, they are still intractable and with enough craypots, it would be impossible to work out a new route before the crayfisher has to move the pots again!

Instead of wasting time on trying to invent a clever algorithm that no-one has been able to find, we need to rely on a algorithm that will generate an approximate solution. The crayfisher would be happy with an approximate solution that is say, 10% longer than the best possible route, but which the computer can find quickly.

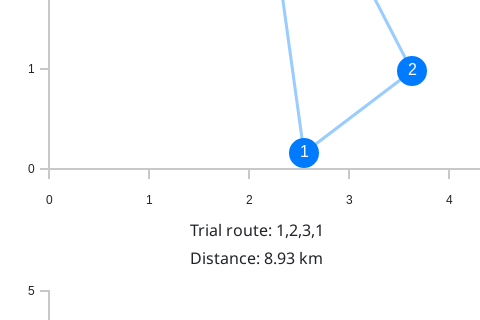

There are several ways of approaching this. Some are better than others in general, and some are better than others with certain layouts. One of the more obvious approximate algorithms, is to start from the boat dock in the top left corner of your map and to go to the nearest craypot. From there, you should go to the nearest craypot from that craypot, and repeatedly go to the nearest craypot that hasn’t yet been checked. This approach is known as a greedy heuristic algorithm as it always makes the decision that looks the best at the current time, rather than making a not so good decision now to try and get a bigger pay off later. You will understand why this doesn’t necessarily lead to the optimal solution after completing the following exercises.

On a copy of each of the two maps you generated, draw lines between the craypots to show the route you would find following the greedy algorithm (you should have made more than one copy of each of the maps!)

For your map with the smaller number of craypots (7 or 8), compare your optimal solution and your approximate solution. Are they the same? Or different? If they are the same, would they be the same in all cases? Show a map where they would be different (you can choose where to place the craypots yourself, just use as many craypots as you need to illustrate the point).

For your larger map, show why you don’t have an optimal solution. The best way of doing this is to show a route that is similar to, but shorter than the approximate solution. The shorter solution you find doesn’t have to be the optimal solution, it just has to be shorter than the one identified by the approximate algorithm. Talk to your teacher if you can’t find a shorter route and they will advise on whether or not you should generate a new map. You will need to show a map that has a greedy route and a shorter route marked on it. Explain the technique you used to show there was a shorter solution. Remember that it doesn’t matter how much shorter the new solution you identify is, just as long as it is at least slightly shorter than the approximate solution – you are just showing that the approximate solution couldn’t possibly be the optimal solution by showing that there is a shorter solution than the approximate solution.

Even though the greedy algorithm only generates an approximate solution, as opposed to the optimal solution, explain why is it more suitable for the crayfisher than generating an optimal solution would be?

Why would it be important to the crayfisher to find a short route between the craypots, as opposed to just visiting them in a random order? Discuss other problems that are equivalent to TSP that real world companies encounter every day. Why is it important to these companies to find good solutions to TSP? Estimate how much money a courier company might be wasting over a year if their delivery routes were 10% worse than the optimal. How many different locations/towns/etc might their TSP solutions have to be able to handle?

Find a craypot layout that results in the greedy algorithm finding what seems to be a really inefficient route. Why is it inefficient? Don’t worry about trying to find an actual worst case, just find a case that seems to be quite bad. What is a general pattern that seems to make this greedy algorithm inefficient?

Don't forget to include an introductory paragraph in your report that outlines the key ideas. It should include a brief description of what an intractable problem is, and how a computer scientist goes about dealing with such a problem. The report should also describe the travelling salesman problem and the craypot problem in your own words. Explain why the craypot problem is a realistic problem that might matter to someone.