Having all the sliders at the extremes will produce black and white, and if they are all the same value but in between, it will be grey (i.e. between black and white).

Yellow is not what you might expect – it's made from red and green, with no blue.

In school or art class you may have mixed different colours of paint or dye together in order to make new colours. In painting it's common to use red, yellow and blue as three "primary" colours that can be mixed to produce lots more colours. Mixing red and blue give purple, red and yellow give orange, and so on. By mixing red, yellow, and blue, you can make many new colours.

For printing, printers commonly use three slightly different primary colours: cyan, magenta, and yellow (CMY). All the colours on a printed document were made by mixing these primary colours.

Both these kinds of mixing are called "subtractive mixing", because they start with a white canvas or paper, and "subtract" colour from it. The interactive below allows you to experiment with CMY in case you are not familiar with it, or if you just like mixing colours.

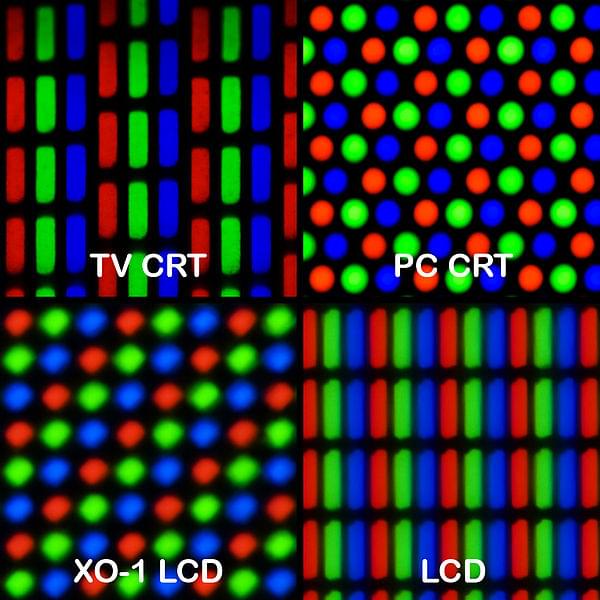

Computer screens and related devices also rely on mixing three colours, except they need a different set of primary colours because they are additive, starting with a black screen and adding colour to it. For additive colour on computers, the colours red, green and blue (RGB) are used. Each pixel on a screen is typically made up of three tiny "lights"; one red, one green, and one blue. By increasing and decreasing the amount of light coming out of each of these three, all the different colours can be made. The following interactive allows you to play around with RGB.

See what colours you can make with the RGB interactive. Can you make black, white, shades of grey, yellow, orange, and purple?

Having all the sliders at the extremes will produce black and white, and if they are all the same value but in between, it will be grey (i.e. between black and white).

Yellow is not what you might expect – it's made from red and green, with no blue.

There's a very good reason that we mix three primary colours to specify the colour of a pixel. The human eye has millions of light sensors in it, and the ones that detect colour are called "cones". There are three different kinds of cones, which detect red, blue, and green light respectively. Colours are perceived by the amount of red, blue, and green light in them. Computer screen pixels take advantage of this by releasing the amounts of red, blue, and green light that will be perceived as the desired colour by your eyes. So when you see "purple", it's really the red and blue cones in your eyes being stimulated, and your brain converts that to a perceived colour. Scientists are still working out exactly how we perceive colour, but the representations used on computers seem to be good enough give the impression of looking at real images.

For more information about RGB displays, see RGB on Wikipedia; for more information about the eye sensing the three colours, see Cone cell and trichromacy on Wikipedia.

Because a colour is simply made up of amounts of the primary colours (red, green and blue), three numbers can be used to specify how much of each of these primary colours is needed to make the overall colour.

The word pixel is short for "picture element". On computer screens and printers an image is almost always displayed using a grid of pixels, each one set to the required colour. A pixel is typically a fraction of a millimeter across, and images can be made up of millions of pixels (one megapixel is a million pixels), so you can't usually see the individual pixels. Photographs commonly have several megapixels in them.

It's not unusual for computer screens to have millions of pixels on them, and the computer needs to represent a colour for each one of those pixels.

A commonly used scheme is to use numbers in the range 0 to 255. Those numbers tell the computer how fully to turn on each of the primary colour "lights" in an individual pixel. If red was set to 0, that means the red "light" is completely off. If the red "light" was set to 255, that would mean the "light" was fully on.

With 256 possible values for each of the three primary colours (don't forget to count 0!), that gives 256 x 256 x 256 = 16,777,216 possible colours – more than the human eye can detect!

Think back to the binary numbers section. What is special about the number 255, which is the maximum colour value?

We'll cover the answer later in this section if you are still not sure!

The following interactive allows you to zoom in on an image to see the pixels that are used to represent it. Each pixel is a solid colour square, and the computer needs to store the colour for each pixel. If you zoom in far enough, the interactive will show you the red-green-blue values for each pixel. You can pick a pixel and put the values on the slider above – it should come out as the same colour as the pixel.

The next thing we need to look at is how bits are used to represent each colour in a high quality image. Firstly, how many bits do we need? Secondly, how should we decide the values of each of those bits? This section will work through those problems.

With 256 different possible values for the amount of each primary colour, this means 8 bits would be needed to represent the number.

The smallest number that can be represented using 8 bits is 00000000 – which is 0. And the largest number that can be represented using 8 bits is 11111111 – which is 255.

Because there are three primary colours, each of which will need 8 bits to represent each of its 256 different possible values, we need 24 bits in total to represent a colour.

So, how many colours are there in total with 24 bits? We know that there is 256 possible values each colour can take, so the easiest way of calculating it is:

This is the same as .

Because 24 bits are required, this representation is called 24 bit colour. 24 bit colour is sometimes referred to in settings as "True Color" (because it is more accurate than the human eye can see). On Apple systems, it is called "Millions of colours".

A logical way is to use 3 binary numbers that represent the amount of each of red, green, and blue in the pixel. In order to do this, convert the amount of each primary colour needed to an 8 bit binary number, and then put the 3 binary numbers side by side to give 24 bits.

Because consistency is important in order for a computer to make sense of the bit pattern, we normally adopt the convention that the binary number for red should be put first, followed by green, and then finally blue. The only reason we put red first is because that is the convention that most systems assume is being used. If everybody had agreed that green should be first, then it would have been green first.

For example, suppose you have the colour that has red = 145, green = 50, and blue = 123 that you would like to represent with bits. If you put these values into the interactive, you will get the colour below.

Start by converting each of the three numbers into binary, using 8 bits for each.

You should get: - red = 10010001, - green = 00110010, - blue = 01111011.

Putting these values together gives 100100010011001001111011, which is the bit representation for the colour above.

There are no spaces between the three numbers, as this is a pattern of bits rather than actually being three binary numbers, and computers don’t have any such concept of a space between bit patterns anyway – everything must be a 0 or a 1. You could write it with spaces to make it easier to read, and to represent the idea that they are likely to be stored in 3 8-bit bytes, but inside the computer memory there is just a sequence of high and low voltages, so even writing 0 and 1 is an arbitrary notation.

Also, all leading and trailing 0’s on each part are kept – without them, it would be representing a shorter number. If there were 256 different possible values for each primary colour, then the final representation must be 24 bits long.

"Black and white" images usually have more than two colours in them; typically 256 shades of grey, represented with 8 bits.

Remember that shades of grey can be made by having an equal amount of each of the 3 primary colours, for example red = 105, green = 105, and blue = 105.

So for a monochromatic image, we can simply use a representation which is a single binary number between 0 and 255, which tells us the value that all 3 primary colours should be set to.

The computer won’t ever convert the number into decimal, as it works with the binary directly – most of the process that takes the bits and makes the right pixels appear is typically done by a graphics card or a printer. We just started with decimal because it is easier for humans to understand. The main point about knowing this representation is to understand the trade-off that is being made between the accuracy of colour (which should ideally be beyond human perception) and the amount of storage (bits) needed (which should be as little as possible).

If you haven't already, read the subsection on hexadecimal in the numbers section, otherwise this section might not make sense!

When writing HTML code, you often need to specify colours for text, backgrounds, and so on. One way of doing this is to specify the colour name, for example "red", "blue", "purple", or "gold". For some purposes, this is okay.

However, the use of names limits the number of colours you can represent and the shade might not be exactly the one you wanted.

A better way is to specify the 24 bit colour directly.

Because 24 binary digits are hard to read, colours in HTML use hexadecimal codes as a quick way to write the 24 bits, for example #00FF9E.

The hash sign means that it should be interpreted as a hexadecimal representation, and since each hexadecimal digit corresponds to 4 bits, the 6 digits represent 24 bits of colour information.

This "hex triplet" format is used in HTML pages to specify colours for things like the background of the page, the text, and the colour of links. It is also used in CSS, SVG, and other applications.

In the 24 bit colour example earlier, the 24 bit pattern was 100100010011001001111011.

This can be broken up into groups of 4 bits: 1001 0001 0011 0010 0111 1011.

And now, each of these groups of 4 bits will need to be represented with a hexadecimal digit.

Which gives #91327B.

Understanding how these hexadecimal colour codes are derived also allows you to change them slightly without having to refer back to the colour table, when the colour isn’t exactly the one you want. Remember that in the 24 bit color code, the first 8 bits specify the amount of red (so this is the first 2 digits of the hexadecimal code), the next 8 bits specify the amount of green (the next 2 digits of the hexadecimal code), and the last 8 bits specify the amount of blue (the last 2 digits of the hexadecimal code). To increase the amount of any one of these colours, you can change the appropriate hexadecimal characters.

For example, #000000 has zero for red, green and blue, so setting a higher value to the middle two digits (such as #004300) will add some green to the colour.

You can use this HTML page to experiment with hexadecimal colours. Just enter a colour in the space below:

What if we were to use fewer than 24 bits to represent each colour? How much space will be saved, compared to the impact on the image?

The following interactive gets you to try and match a specific colour using 24 bits, and then 8 bits.

It should be possible to get a perfect match using 24 bit colour. But what about 8 bits?

The above system used 3 bits to specify the amount of red (8 possible values), 3 bits to specify the amount of green (again 8 possible values), and 2 bits to specify the amount of blue (4 possible values). This gives a total of 8 bits (hence the name), which can be used to make 256 different bit patterns, and thus can represent 256 different colours.

You may be wondering why blue is represented with fewer bits than red and green. This is because the human eye is the least sensitive to blue, and therefore it is the least important colour in the representation. The representation uses 8 bits rather than 9 bits because it's easiest for computers to work with full bytes.

Using this scheme to represent all the pixels of an image takes one third of the number of bits required for 24-bit colour, but it is not as good at showing smooth changes of colours or subtle shades, because there are only 256 possible colors for each pixel. This is one of the big tradeoffs in data representation: do you allocate less space (fewer bits), or do you want higher quality?

The number of bits used to represent the colours of pixels in a particular image is sometimes referred to as its "colour depth" or "bit depth". For example, an image or display with a colour depth of 8-bits has a choice of 256 colours for each pixel. There is more information about this on Wikipedia. Drastically reducing the bit depth of an image can make it look very strange; sometimes this is used as a special effect called "posterisation" (ie. making it look like a poster that has been printed with just a few colours).

There's a subtle boundary between low quality data representations (such as 8-bit colour) and compression methods. In principle, reducing an image to 8-bit colour is a way to compress it, but it's a very poor approach, and a proper compression method like JPEG will do a much better job.

The following interactive shows what happens to images when you use a smaller range of colours (including right down to zero bits!). You can choose an image using the menu or upload your own one. In which cases is the change in quality most noticeable? In which is it not? In which would you actually care about the colours in the image? In which situations is colour actually not necessary (i.e. when are we fine with two colours)?

Although we provide a simple interactive for reducing the number of bits in an image, you could also use software like Gimp or Photoshop to save files with different colour depths.

You probably noticed that 8-bit colour looks particularly bad for faces, where we are used to seeing subtle skin tones. Even the 16-bit colour is noticably worse for faces.

In other cases, the 16-bit images are almost as good as 24-bit images unless you look really carefully. They also use two-thirds (16/24) of the space that they would with 24-bit colour. For images that will need to be downloaded on 3G devices where internet is expensive, this is worth thinking about carefully.

Have an experiment with the following interactive, to see what impact different numbers of bits for each colour has. Do you think 8 bit colour was right in having 2 bits for blue, or should it have been green or red that got only 2 bits?

One other interesting thing to think about is whether or not we’d want more than 24 bit colour. It turns out that the human eye can only differentiate around 10 million colours, so the ~ 16 million provided by 24 bit colour is already beyond what our eyes can distinguish. However, if the image were to be processed by some software that enhances the contrast, it may turn out that 24-bit colour isn't sufficient. Choosing the representation isn't simple!

An image represented using 24 bit colour would have 24 bits per pixel. In 600 x 800 pixel image (which is a reasonable size for a photo), this would contain pixels, and thus would use bits. This works out to around 1.44 megabytes. If we use 8-bit colour instead, it will use a third of the memory, so it would save nearly a megabyte of storage. Or if the image is downloaded then a megabyte of bandwidth will be saved.

8 bit colour is not used much anymore, although it can still be helpful in situations such as accessing a computer desktop remotely on a slow internet connection, as the image of the desktop can instead be sent using 8 bit colour instead of 24 bit colour. Even though this may cause the desktop to appear a bit strange, it doesn’t stop you from getting whatever it was you needed to get done, done. Seeing your desktop in 24 bit colour would not be very helpful if you couldn't get your work done!

In some countries, mobile internet data is very expensive. Every megabyte that is saved will be a cost saving. There are also some situations where colour doesn’t matter at all, for example diagrams, and black and white printed images.

If space really is an issue, then this crude method of reducing the range of colours isn't usually used; instead, compression methods such as JPEG, GIF and PNG are used.

These make much more clever compromises to reduce the space that an image takes, without making it look so bad, including choosing a better palette of colours to use rather than just using the simple representation discussed above. However, compression methods require a lot more processing, and images need to be decoded to the representations discussed in this chapter before they can be displayed.

The ideas in this present chapter more commonly come up when designing systems (such as graphics interfaces) and working with high-quality images (such as RAW photographs), and typically the goal is to choose the best representation possible without wasting too much space.

Have a look at the compression chapter to find out more!